Astronomical alignments at Stonehenge.

When were alignments first noticed in modern times?

The local stories say that people have been gathering at Stonehenge at midsummer back into the mists of time, but it wasn't until 1740 that William Stukeley noted that:

“The Avenue . . . answers, as we have said before, to the principal line of the whole work, the north-east, whereabouts the sun rises, when the days are longest”

Subsequent authors, originally Dr. John Smith in 1771, made the incorrect assumption that it was the Heel Stone itself that marked the position of sunrise on the longest day - the 21st June.

In reality, the Heel Stone is not exactly in the middle of the Avenue – it's offset to the east - and so it doesn't indicate where the first gleam of the Sun appeared over the horizon 4,500 years ago.

Back when Stonehenge was built the Earth's axis was tilted over slightly more at 24° instead of the 23.5° it is today. The difference means that originally the Sun rose much further to the left of the Heel Stone than it does today – by about two whole sun-widths.

Where does the sun rise over Stonehenge now?

Nowadays, the trees on the horizon add to the problem and the Sun seems to rise directly  out of the tip of the Heel Stone rather than to its left at Summer Solstice. out of the tip of the Heel Stone rather than to its left at Summer Solstice.

When conditions are perfectly clear, the Heel Stone casts a long shadow that penetrates the Sarsen Circle through the main entrance. Without the trees and the change in the Earth's tilt, this shadow effect would have been far more noticeable 4,500 years ago.

Some have chosen to see this as the symbolic fertilisation of the Earth Goddess (personified by the Sarsen Circle) by the Sky God (the shadow of the Heel Stone created by the Sun at the height of his power).

Whatever the truth of that interpretation, it's certainly the case that 9 months afterwards we reach the Vernal Equinox and the rebirth of the land in springtime.

Where does the sun set on the winter solstice at Stonehenge?

Archaeologists now firmly believe that it was the Winter Solstice Sunset that was the important time of year for the builders of Stonehenge, and this is in exactly the opposite direction to that of the Summer Solstice Sunrise.

When viewed from the centre line of the Avenue, next to the Heel Stone, the Sun on the shortest day (around the 22nd December) would have been seen to set in the southwest between the uprights of the tallest Trilithon at Stonehenge.

Once again, in our era there are trees obscuring the horizon beyond Stonehenge in that direction plus a metal bridge in the way across the top of the Avenue.

If you know where to stand the effect is still spectacular even though only one of the uprights is still standing. Here's the free view from the National Trust field near the top of the Avenue:

… and here's the paying visitors' view from the walkway itself.

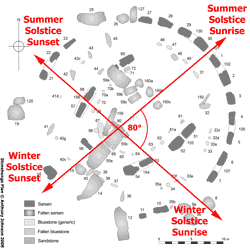

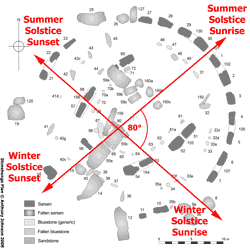

These two directions – Summer Solstice Sunrise and  Winter Solstice Sunset – make up the primary alignment at Stonehenge. This runs roughly northeast-southwest and the Avenue follows it for the first few hundred yards of its length down the slope away from the monument beyond the Heel Stone. Winter Solstice Sunset – make up the primary alignment at Stonehenge. This runs roughly northeast-southwest and the Avenue follows it for the first few hundred yards of its length down the slope away from the monument beyond the Heel Stone.

Are there any other important alignments?

In the last 20 years, entirely as a result of the work by Prof. Gordon Freeman of the University of Alberta, a secondary alignment has been suggested that runs between the Winter Solstice Sunrise and the Summer Solstice Sunset.

This alignment makes use of a sightline that goes through a “notch” in the edge of one of the stones of the western Trilithon, skims the edge of one of the stones of the  southeastern Trilithon and passes between the stones on either side of the Sarsen Circle. southeastern Trilithon and passes between the stones on either side of the Sarsen Circle.

Here's the view from the visitor path closest to the Sarsen Circle, looking southeast along this secondary alignment.

A close-up view shows the horizon over Coneybury Hill

and this is exactly where Winter Solstice Sunrise occurred 4,500 years ago:

Because the Earth's axis has changed its tilt slightly the Winter Solstice Sunrise now occurs two sun-widths to the left of where it did when Stonehenge was built. This means that this very precise alignment is now a little off. Because the Earth's axis has changed its tilt slightly the Winter Solstice Sunrise now occurs two sun-widths to the left of where it did when Stonehenge was built. This means that this very precise alignment is now a little off.

Even so, you only have to wait a few minutes after sunrise for the Sun to shine straight along this line.

And the view from slightly further back is breathtaking.

Of course, in the same way that the reverse direction of the Summer Sunrise is the Winter Sunset, the reverse of the Winter Sunrise is the Summer Sunset as shown left.

This means that looking from the southeast side of the circle, the Summer Solstice Sunset should be visible through the same notch but in the opposite direction, which it is – although the fallen lintel of the tallest Trilithon gets in the way a bit.

These two alignments intersect inside the Sarsen Circle in an interesting way. They cross at 80° directly over the centre of the Altar Stone, which lies exactly along the secondary alignment.

Even more strangely, this 80° angle is echoed  in one of the most astonishing pieces of Bronze Age goldwork ever discovered in Britain, from a barrow within sight of Stonehenge - the famous Bush Barrow Lozenge which is now in Wiltshire Museum at Devizes. in one of the most astonishing pieces of Bronze Age goldwork ever discovered in Britain, from a barrow within sight of Stonehenge - the famous Bush Barrow Lozenge which is now in Wiltshire Museum at Devizes.

Is this a coincidence, or did the builders of Stonehenge and those that came after them seek to encode their understanding of the angles between Solstices sunrises and sunsets in their monument and their jewels?

That's a question that will probably forever remain unanswered.

Are there any lunar alignments at Stonehenge?

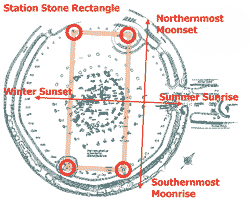

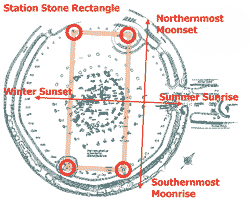

Apart from these solar alignments, there are also alignments to the Moon.These were first pointed out by C.A. “Peter” Newham in the 1960s and are encoded by the Station Stone Rectangle.

There were originally four Station Stones, but only two remain on site. The positions of the missing ones are known from excavation and geophysics work.

The short sides of this rectangle are parallel to the main alignment from Summer  Solstice Sunrise to Winter Solstice Sunset. Solstice Sunrise to Winter Solstice Sunset.

The long sides point towards the positions of the Southernmost Moonrise and Northernmost Moonset – and the Moon only reaches these positions every 18.6 years.

What's more, it's only at the latitude of Stonehenge (give or take 30 miles or so) that these lunar and solar extreme positions make a right angle. Go further north or south and the Station Stone Rectangle would become a slightly squashed parallelogram.

Some archaeologists and astronomers dispute that the Station Stone Rectangle intentionally marks these lunar alignments, but given the attention that the extreme positions of the Moon attracts at other neolithic sites in the British Isles and elsewhere we are perhaps doing the Stonehenge builders an injustice if we doubt their ability to mark these points.

The next time that the Moon will reach these extreme positions will be in 2025, so let's hope that the southernmost Moonrise nearest the Summer Solstice and northernmost Moonset nearest the Winter Solstice will enjoy clear skies.

I'll see you there.

Simon Banton

Archaeoastronomer

Stonehenge's astronomical

orientations towards midwinter solstice

sunset and midsummer solstice sunrise are not particularly unique – similar arrangements

were made at earlier monuments,

such as the passage tombs of Maes Howe in

Orkney and Newgrange in Ireland – but what

is unmatched is the concentration of solstice

sunrise/sunset aligned monuments in the

Stonehenge environs, including Durrington

Walls’ Avenue and its Northern Circle and

Southern Circle, as well as Woodhenge and

Coneybury henge.

For visits inside Stonehenge to see where these alignments are please refer to our Stonehenge Special access page

Back to Home page |

out of the tip of the Heel Stone rather than to its left at Summer Solstice.

out of the tip of the Heel Stone rather than to its left at Summer Solstice.

Winter Solstice Sunset – make up the primary alignment at Stonehenge. This runs roughly northeast-southwest and the Avenue follows it for the first few hundred yards of its length down the slope away from the monument beyond the Heel Stone.

Winter Solstice Sunset – make up the primary alignment at Stonehenge. This runs roughly northeast-southwest and the Avenue follows it for the first few hundred yards of its length down the slope away from the monument beyond the Heel Stone. southeastern Trilithon and passes between the stones on either side of the Sarsen Circle.

southeastern Trilithon and passes between the stones on either side of the Sarsen Circle.

Because the Earth's axis has changed its tilt slightly the Winter Solstice Sunrise now occurs two sun-widths to the left of where it did when Stonehenge was built. This means that this very precise alignment is now a little off.

Because the Earth's axis has changed its tilt slightly the Winter Solstice Sunrise now occurs two sun-widths to the left of where it did when Stonehenge was built. This means that this very precise alignment is now a little off.

in one of the most astonishing pieces of Bronze Age goldwork ever discovered in Britain, from a barrow within sight of Stonehenge - the famous Bush Barrow Lozenge which is now in Wiltshire Museum at Devizes.

in one of the most astonishing pieces of Bronze Age goldwork ever discovered in Britain, from a barrow within sight of Stonehenge - the famous Bush Barrow Lozenge which is now in Wiltshire Museum at Devizes. Solstice Sunrise to Winter Solstice Sunset.

Solstice Sunrise to Winter Solstice Sunset.